“I play golf every day. That’s part of my routine,” says Javed Burki as we walk around his house in one of the elite neighbourhoods of Islamabad. It has been raining for the past few days, causing the temperature to drop further. As he takes me to his garden, Burki introduces me to his pet dog, Shadow.

“Be careful, he is very friendly, but if you ignore him, he will start jumping,” Burki smiles before engaging in a game of throw-ball with his pet. A former Pakistan captain, erstwhile chief national selector, and civil servant, Burki will turn 87 in a couple of months. But age, clearly, has not caught up with him.

The word ‘discipline’ repeatedly comes up in our conversation as Burki turns back the clock and recalls his first visit to India with the Pakistan Test team in December 1960. He was just 22 then and among the youngest members of the squad, led by the legendary Fazal Mahmood.

All five Test matches in the series ended in a draw — unimaginable in today’s era. “But those days were different,” he says. “Even after the India series, when we played against Australia and New Zealand, it was the same story — we did not win, we did not lose, but we drew…”

Four months before the team left for India, Burki returned to Pakistan from England to prepare for the civil services examination in November. “Around October, they held trials to select the team for India. I was picked, but I told the selectors I would not be available for the first few tour matches due to the examination,” he says.

Years after retiring, Burki returned as chief selector, overseeing Pakistan’s 1992 World Cup-winning squad led by his cousin, Imran Khan.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Photo Archives

Years after retiring, Burki returned as chief selector, overseeing Pakistan’s 1992 World Cup-winning squad led by his cousin, Imran Khan.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Photo Archives

Once the examination was over in late November, he arrived in Bombay — modern-day Mumbai — for the first Test. But Burki faced an unexpected challenge upon checking in at the Cricket Club of India premises. “Since returning from England, I had been busy preparing for the civil service examination. As a result, I hadn’t been exposed to much of the subcontinental sun. And in Bombay, the sun was so bright that I felt very uncomfortable,” he remembers.

He requested that the team management not consider him for the first test at the Brabourne Stadium. “I wanted to acclimatise. But the team management rejected my request and said I’d have to play…”

It was not an outing to remember, as he scored just seven runs in the first innings before falling to Subhash Gupte. Though he remained unbeaten on 13 in the second, Burki did not have much to write home about.

But off the pitch, there were memorable moments.

Starry experiences

“Yusuf Khan, who?”

Burki remembers asking a gentleman this question at a party hosted by the noted filmmaker and producer Mehboob Khan in Bombay. The gentleman appeared awkward, as Burki failed to recognise him. “The first day, he introduced himself as Dilip Kumar, and a couple of days later, he walked up to me and said, ‘I am Yusuf Khan, remember me?’ And my answer was —‘no’…” Burki says with a smile.

Back then, Burki was unaware that Dilip — the revered actor — was originally known as Yusuf Khan. “And that led to the confusion. But he was a very nice man, and we had a great time discussing his roots in Peshawar and his family,” he recalls.

During that tour, Burki also met yesteryear actors Ashok Kumar and Raj Kapoor, as well as the illustrious Saira Banu, who later married Dilip. “Back then, they weren’t married. And when we were in Bombay, Fazal (Mahmood) and I socialised with many people from the film industry, and it was a great experience,” he recollects. From Bombay, the journey continued to Kanpur. In those days, air travel wasn’t the norm, and Burki recalls that separate train bogies were reserved for the Indian and Pakistan teams. “There was a different excitement,” he says.

Once the second Test got underway in Kanpur, Burki played a gritty innings of 79 before being run out. “On that tour, I always contributed when my team was in trouble, and the innings in Kanpur was one such occasion,” he says. “When we played the fourth Test in Madras (now Chennai), the wicket had become very easy to bat on. By the time my turn came, I had no interest, and I was out quickly… But I always performed under pressure.”

While he recalls that most wickets were placid, the one at Eden Gardens favoured the bowlers. “I thought this was a Test where we could maybe get India on the run. It was a wicket where he (Mahmood) could work. On the other grassless turf wickets, he couldn’t do anything. But in Calcutta, where the ball gripped a little, I thought we could get things done. So when I went in, I went for the Indian bowling and played a quickfire innings,” he says.

However, Pakistan’s captain, Mahmood, did not press for a win. “Back in those days, the mentality was to not lose. And we were not trying to win. Both teams were afraid of losing…” Burki remembers how the Pakistan batters looked comfortable against India’s medium pacers, Surendra Nath and Ramakant Desai.

Before breaking into the Pakistan team, Burki had played against a touring Indian team for Oxford, where he scored a century.

“That experience helped. I had previously played against Gupte and Chandu Borde, so I’d already seen all these boys on a sporting wicket in Oxford. And here I was, playing against them on these very easy wickets. So it wasn’t much of a problem,” he says.

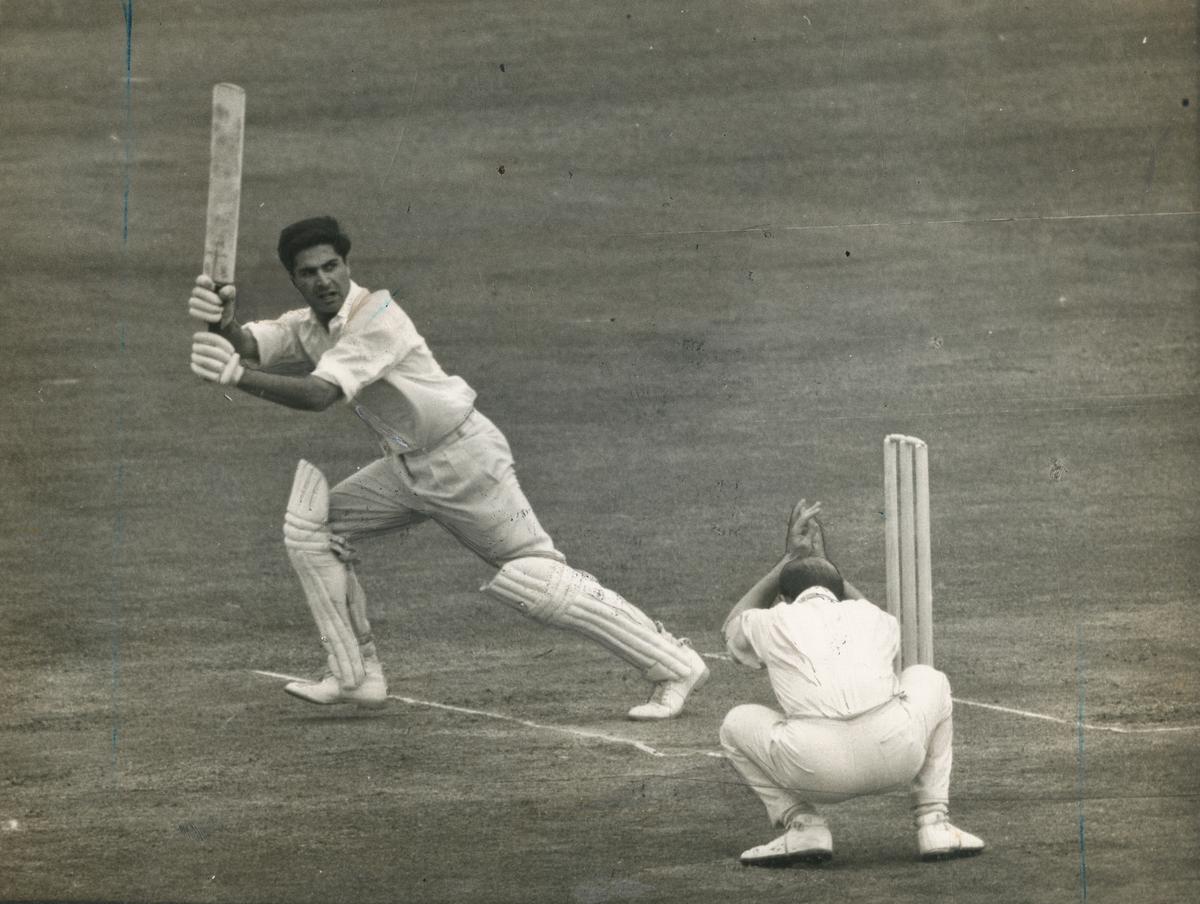

Pakistan captain Javed Burki plays a shot off Leonard Coldwell during his century stand with Nasim-ul-Ghani (101). Their 197-run partnership saved Pakistan from an innings defeat at Lord’s in 1962.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Photo Archives

Pakistan captain Javed Burki plays a shot off Leonard Coldwell during his century stand with Nasim-ul-Ghani (101). Their 197-run partnership saved Pakistan from an innings defeat at Lord’s in 1962.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Photo Archives

Feeling at home

The touring team had little trouble adapting to conditions, but the Pakistan players encountered an unforeseen predicament upon arriving in Madras for the fourth Test — finding familiar food. “Some of us from the north, northwest, were not able to eat too much rice. We were sort of wheat eaters. And in Madras in those days, nobody had ever heard of chapati. We tried to explain to the gentleman in the kitchen, and they whipped up something from white flour,” Burki recalls, adding, “We ended up eating a lot of rice…”

Wall of Legacy: Javed Burki’s picture adorns a gallery of Pakistan’s Test captains at Gaddafi Stadium, Lahore.

| Photo Credit:

SHAYAN ACHARYA

Wall of Legacy: Javed Burki’s picture adorns a gallery of Pakistan’s Test captains at Gaddafi Stadium, Lahore.

| Photo Credit:

SHAYAN ACHARYA

Born in Meerut in undivided India, the tour of India felt like a homecoming for Burki. However, as a youngster, it was also about acclimatising to international cricket. “The cultures were not different. And for me, it was not different at all,” he says. “I was born in Meerut, and our family, we were Afghans. We had 12 fortified villages outside Jalandhar, and I came to Pakistan in October or November of 1947 from Lucknow. So this was new for me, but not India, so that tour was a great moment for me,” he adds.

Pakistan’s team at the time was a product of the Ranji Trophy, with several of its players having gained considerable First-Class experience in undivided India. Burki believes that university-level cricket in the United Kingdom also played a significant role in shaping many players.

Sussex captain Ted Dexter and Pakistan skipper Javed Burki at a reception at the Savoy Hotel, London, on April 27, 1962.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Photo Archives

Sussex captain Ted Dexter and Pakistan skipper Javed Burki at a reception at the Savoy Hotel, London, on April 27, 1962.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Photo Archives

Burki made an impressive start to Test cricket, scoring over 650 runs at an average of more than 50 in his first two series. He eventually captained Pakistan on its tour of England in 1962. “I was initially reluctant to accept the role, but I had to accept it since most of the selection committee members were senior civil servants and I was a junior civil servant,” he says with a smile.

Despite playing 177 First-Class matches, Burki featured in only 25 Tests. As he explains, the decision to step away from international cricket was influenced by his flourishing career in civil service.

“The government of Pakistan had a rule that any civil servant who was a member of a national team in any sport had to be given time off to play for the national team, and his time with the national team was considered as on duty. So, they always had to release me for international assignments. After two or three years, it became a little difficult for me because I couldn’t be given good posts,” Burki says.

“That’s when I decided to focus on my job, and cricket took a backseat. I could never really become a full-time cricketer mainly because of my job, and also since there wasn’t much cricket, there was just not enough money here,” he says. Over the course of his long career as a civil servant, Burki went on to serve the Government of Pakistan as Secretary in the Ministry of Water and Power.

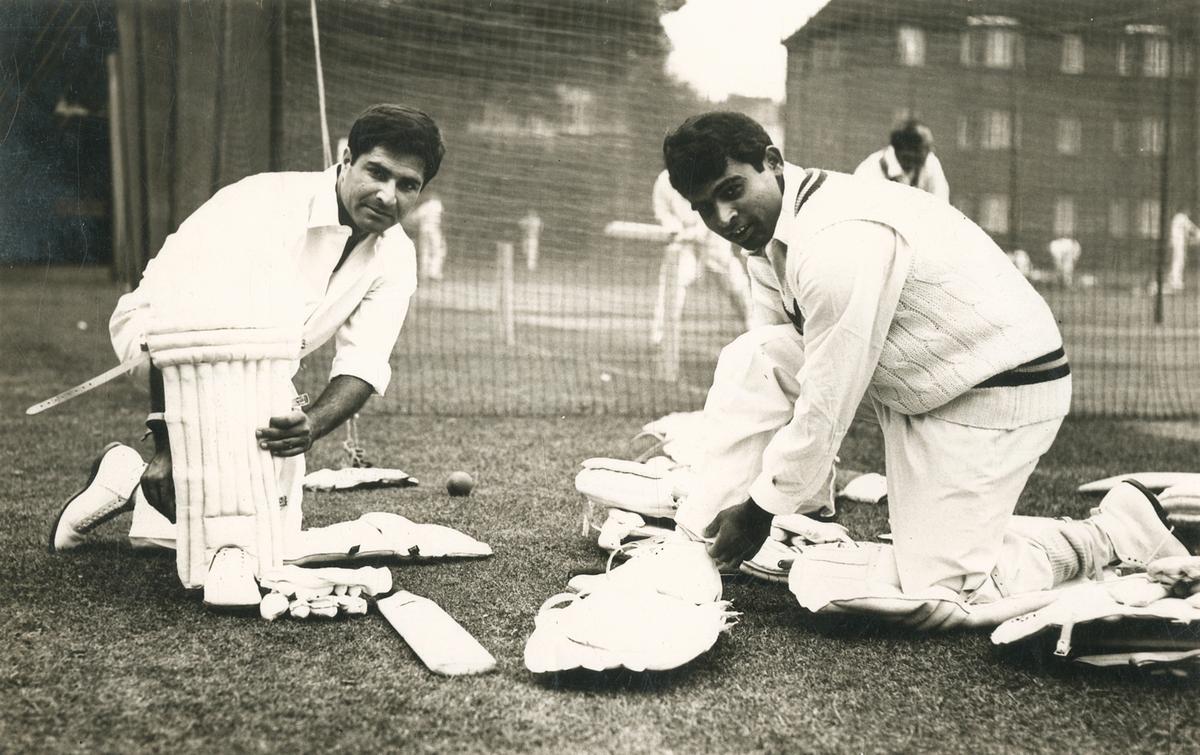

Shortly after arriving in London for the 1962 tour, the Pakistan team hit the nets at Lord’s. Captain Javed Burki can be seen padding up for a session.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Photo Archives

Shortly after arriving in London for the 1962 tour, the Pakistan team hit the nets at Lord’s. Captain Javed Burki can be seen padding up for a session.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Photo Archives

Part of history

However, a couple of decades after calling it quits, Burki returned to the game — albeit as the chief selector of the national team, which went on to win the World Cup title in 1992 under the leadership of his cousin, Imran Khan.

During that phase — from 1989 to 1993 — a group of young cricketers, including Inzamam-ul-Haq, Waqar Younis, Saeed Anwar, and Moin Khan, made their international debuts. “Around that time, India U-19 and Sri Lanka A teams were touring Pakistan, and this was an opportunity for me to pick newer players. So, I got together with some managers of Pakistani teams, people who managed the United Bank team, the Habib Bank team, old cricketers, and asked them about young cricketers,” Burki says.

Thus, players like Inzamam and Younis rose through the ranks. With the 1992 World Cup approaching, Imran would regularly call Burki. “Imran used to keep telephoning me from England, asking: Have you found somebody? I would say, yes. When he came, we presented him Waqar Younis, Inzamam and Anwar, who he did not like. But I insisted that Anwar should be considered,” he says.

The rest, of course, is history, as Anwar went on to become one of the icons of Pakistan cricket across formats. Burki also notes that maintaining discipline was never a challenge.

Javed Burki (L) and Mohammed Ilyas pad up in the Lord’s nets.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Photo Archives

Javed Burki (L) and Mohammed Ilyas pad up in the Lord’s nets.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Photo Archives

“The boys knew that anybody who did not perform or was indisciplined would be out of the team. From January 1989, right up to the selection of the team for the World Cup in February 1992, we had this continuity of order and discipline and channels of communication. Nobody could go around us, nobody could go and talk to anybody on the board,” he says. While many among the current generation may not be familiar with his name, Burki recalls an incident from 2006 when former India captain Rahul Dravid wished to meet him during India’s tour of Pakistan. “The team was invited by a local banker for a meal, and Imran was also there. So, he called me to say that the Indian team wanted to meet me.

When I went there, it turned out to be Dravid, who wanted to meet me because he wanted to know about the tour of India in 1960-61 and asked me why the current Pakistan team was different,” Burki says. “I explained that the cultures were now more diverse. Back in the 1960s, the Indian and Pakistani cultures were kind of similar, but now it was different…”

Though he continues to follow Pakistan cricket, and the team’s struggles do disappoint him, Burki, sitting in a cosy corner of his Islamabad home, fondly reminisces about the game’s golden days and the fierce on-field rivalry with the neighbouring nation.

While much of his time is spent with his pet dog and his parrot, Burki often finds himself missing his old friends and the cherished moments of the past.